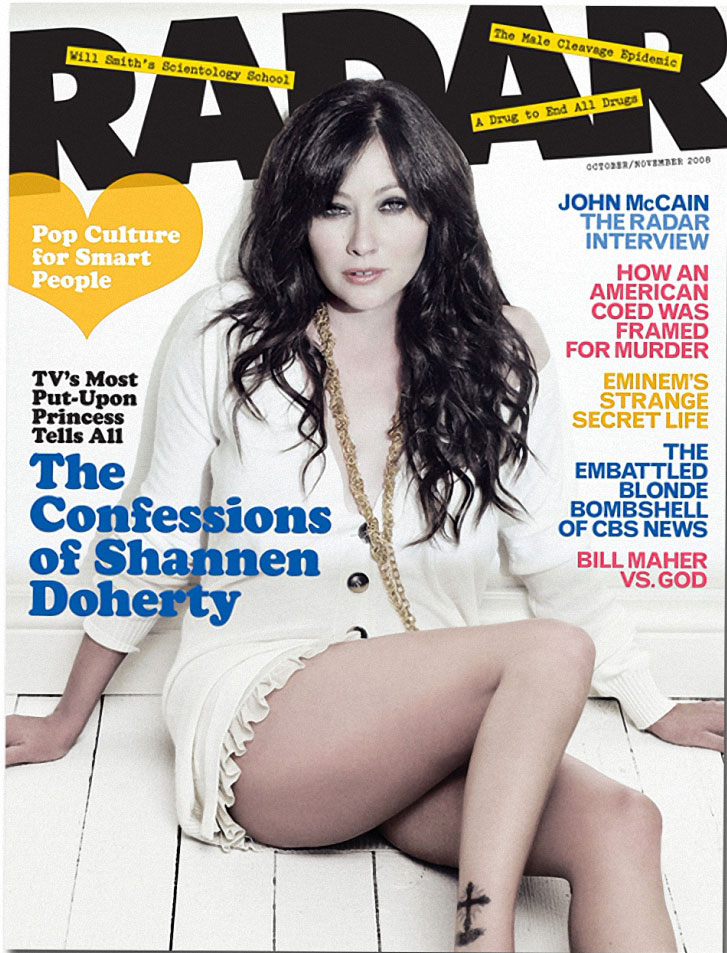

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Cure

An obscure and powerful hallucinogen from Africa might just hold the cure to addiction. So why won’t the government let you have it?

By Tristram Korten

The night B.G. waited for Patrick Kroupa to show up, he felt like he was going to die. After staying clean for 17 years, he had relapsed and spent the last couple of months on a heroin jag. Once again, his body had become so accustomed to the opiates coursing through his blood and into his brain that it stopped producing endorphins, the natural painkillers emitted to block out the daily nuisances of being alive. In the eight hours since his last fix, everyday existence had suddenly become excruciating—his muscles ached; his bones felt brittle; his skin alternated between hot and cold—all of the signals colliding at once, threatening neural overload.

But B.G. (who didn’t want his name or identifying details used) was determined to quit heroin, and Patrick Kroupa was going to help. As instructed, the aging hippie hadn’t scored any junk all day and was entering the phase where just being awake is agony. Withdrawal is the biggest hurdle junkies face when trying to get clean. It’s also the unavoidable reality central to every detoxification regimen there is—except one.

Kroupa, 39 with dirty-blond hair and an oval face, finally arrived at about 9. B.G. lurched to the door, 6 feet, 200 pounds of sweating, quivering misery dressed in a black bathrobe and fuzzy blue slippers. A walrus mustache framed tightly clenched lips.

Kroupa pushed aside the beaded curtain that led into the living room and walked past the black leather couch into the bedroom, with its black carpet and black bed sheets. B.G. asked Kroupa to load the CD player with Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, and the Beatles.

Then Kroupa handed him several capsules containing ibogaine hydrochloride—by his own admission possibly the most dangerous hallucinogen in existence—in a dosage corresponding to B.G.’s body weight. B.G. lay back on his bed, gulped down the pills, and hoped for the best. After the first hour or so, he noticed the pain vanishing. Then the lingering phantom of craving dissipated. And this was just the beginning. For the next eight hours, B.G. was in a deep trance, immersed in a full-on psychedelic trip. He grew quiet as a kaleidoscope of colors, intense images, and memories slipped through his mind. At one point, he began to cry, saying he just wanted to tell his dad that he loved him. At intervals throughout, Kroupa took B.G.’s pulse and made sure he was hydrated. When it was over, B.G. stood up, his long hair mussed, the bathrobe flopping open to reveal boxer trunks askew. He seemed alert and happy. Dawn was breaking outside. “This is fucking beautiful,” he said. “It’s gone, it’s really gone.” And just like that, B.G. was clean. He asked for some chocolate ice cream to celebrate.

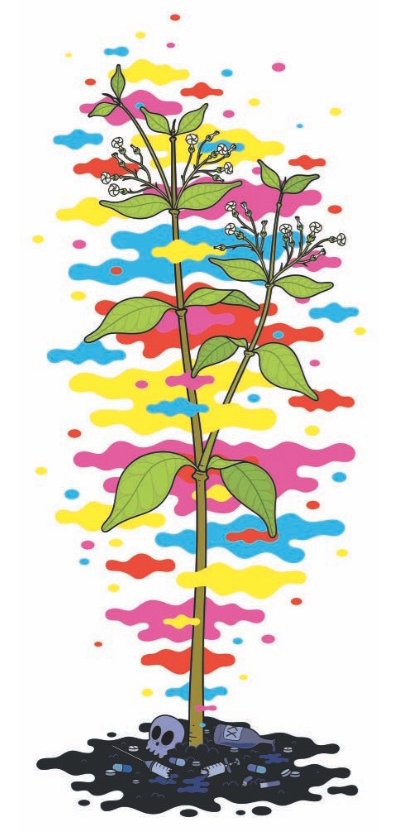

To its proponents in the rehab community, ibogaine is the most important treatment for narcotics addiction ever discovered. The trippy drug with the magical side effect is derived from the bark of the West African shrub Tabernanthe iboga. (Some tribes in Gabon and Cameroon still use the drug as a sacrament.) According to a handful of devoted research scientists, it has proved incredibly effective in alleviating the agonizing effects of withdrawal from a wide array of hard drugs, most notably heroin and cocaine. But to the disappointment of addicts across the country, ibogaine remains strictly illegal, leaving it up to a loosely organized network of activists to distribute the panacea in secret to desperate patients.

Patrick Kroupa is one of those activists; using ibogaine to free the afflicted has become his life’s mission. Dressed in rumpled black clothes, he looks like an overworked grad student as he guides me through his modest stucco home in Coral Gables, Florida, just outside Miami, to the kitchen and offers me a drink. He opens the refrigerator door, revealing shelves stocked with cans of SoBe Adrenaline Rush, Coca-Cola Zero, and milk—for his coffee. “Basically, a lot of variations on caffeine,” he explains. My visit catches him just as he’s packing to move to Woodstock, New York, with his wife, ending an eight-year run here as a research associate at the Brain Endowment Bank, jointly run by University of Miami and the National Parkinson Foundation. The endowment’s director, Dr. Deborah Mash, has been studying ibogaine for almost two decades.

In fact, Kroupa met Dr. Mash, a petite and voluble scientist in her mid-50s, when she treated his own heroin addiction with controlled doses of ibogaine eight years earlier, effectively freeing him from a 16-year habit. It was such a profound experience that Kroupa signed on to help Mash in the laboratory. According to Mash, the drug creates an “immediate cessation of craving.”This is not a cure for addiction, she warns; there are lifestyle and psychological issues at work with each addict. But it provides a very big window of opportunity.

Like Mash, Kroupa has labored to make ibogaine a legal treatment for addicts. In the eyes of the government, however, it remains a dangerous hallucinogen, a Schedule 1 controlled substance that is illegal to use or possess. But its reputed effectiveness has spawned a cult-like following among ex-addicts. The underground movement, made up of volunteer treatment providers like Kroupa who are schooled in ibogaine’s administration, has grown steadily and quietly into an army. Frank Vocci, director of treatment research and development at NIDA (the National Institute on Drug Abuse), a federal agency that funds and monitors narcotics and addiction re- search, has called it “a vast uncontrolled experiment.” Or as Kroupa puts it, “Basically, in any big American city, you can find someone who can get you ibogaine and help you take it.”

Dr. Kenneth Alper, an associate professor of psychiatry and neurology at NewYork University who has chronicled ibogaine’s social evolution, compares the movement with the AIDS group ACT UP in the 1990s. “As with treatments for HIV, ibogaine has been associated with a vocal activist subculture,” he wrote in a 2001 study, “which has viewed its mission as advocating the availability of a controversial treatment to a stigmatized and marginalized minority.” Though their work is illegal, people like Kroupa see themselves as clandestine foot soldiers in a new wave of medical civil disobedience. Today there are ibogaine “scenes” in the Netherlands, Denmark, Great Britain, Italy, France, Slovenia, and Latin America. Still, despite the growing interest, Alper estimates that only 6,000 people worldwide have undergone the treatment.

Basically, in any big American city, you can find someone who can get you ibogaine and help you take it.

–Patrick K. Kroupa

In Kroupa’s cluttered home office, the AC constantly blows at a brisk 62 degrees. “I think better in the cold,” he offers. A silver short-barrel Stoeger Coach shotgun lies on top of a bare mattress tucked against the wall. On a table along another wall is his MacBook Pro, loaded with about $12,000 in additional components. As he maneuvers through his files, which are all encrypted, he is constantly prompted to reenter his password. “I’m paranoid,” he explains— baggage from a former life.

Kroupa is a first-generation computer geek. As a teenager, he went by the cyber sobriquet Lord Digital and helped found the online- hacker and “phone phreak” group Legion of Doom, which famously ravaged the databases of major corporations like AT&T. By 1992, at age 23, Kroupa had turned his computer exploits into something tangible by cofounding MindVox, one of the first Internet service providers on the planet (back when domain names had to be registered with the Department of Defense). MindVox raked in thousands of dollars a month in consulting fees (they brought Playboy, among other companies, online). Kroupa drove a BMW and flew all over the world, dressed in Armani. At the same time, he was spending as much as $1,000 a day on heroin and cocaine, disappearing for weeks at a time into a narcotic oblivion. Kroupa says he still remembers the sensation of his first experience with heroin, at age 14. “It was, ‘This is what it feels like not to hurt; this is what it feels like to be normal,’” he recalls. “All the noise in my head stopped and everything was perfect.”

By 29 the car, clothes, and money were gone, and Kroupa was homeless. On the evening of his 30th birthday, he was arrested for possession of heroin in Manhattan. “I turned 30 in the Tombs,” he says, referring to the notorious jail beneath the criminal courthouse. In the dank concrete cell, the magnitude of what he had lost overwhelmed him, and he resolved to quit.

It wouldn’t be his first effort. “I probably tried 18 to 20 medically supervised detox programs over the years, and maybe another 75 do-it-yourself attempts,” he says. Among the programs he tried: substitution therapies like methadone and buprenorphine, which replace heroin with a milder opiate; ultra-rapid detox, in which the addict is anesthetized to help with the withdrawal process; and a medical procedure using a TENS unit in which electrical currents stimulate the brain. But with each method, withdrawal was unavoidable, and Kroupa winces at the memories: “All of them just meant pain, real pain.” And none of them worked.

Then he heard about Dr. Mash, who ran a treatment center on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. In October 1999 Kroupa rounded up the $10,000 necessary to enroll. When he first arrived, he was in the throes of withdrawal— cramping, cold sweats. “My spine felt like it was being crushed,” he recalls.

Kroupa’s treatment consisted of wearing a blindfold on a bed in a darkened room, listen- ing to soothing music through earphones, and ingesting about 12 milligrams per kilogram of body weight of ibogaine hydrochloride in capsule form, all the while attached to a bank of machines that monitored his vital signs. “Within 30 to 35 minutes, this ball of heat went up my spine and the pain just let go,” Kroupa recounts. “Nothing has ever done that. It was like my habit was a bad dream, a mirage. And before I can focus on what just happened, I start tripping. Eight and a half hours later, they take the blinds off.”

Kroupa says he felt cured. He no longer craved heroin. But it didn’t change 16 years of behavioral patterns that led him to heroin in the first place. On his way back to the U.S., Kroupa’s plane stopped over in Puerto Rico, and he promptly copped a bag of heroin. A month later, strung out again, he returned to St. Kitts for another treatment. He’s been clean ever since.

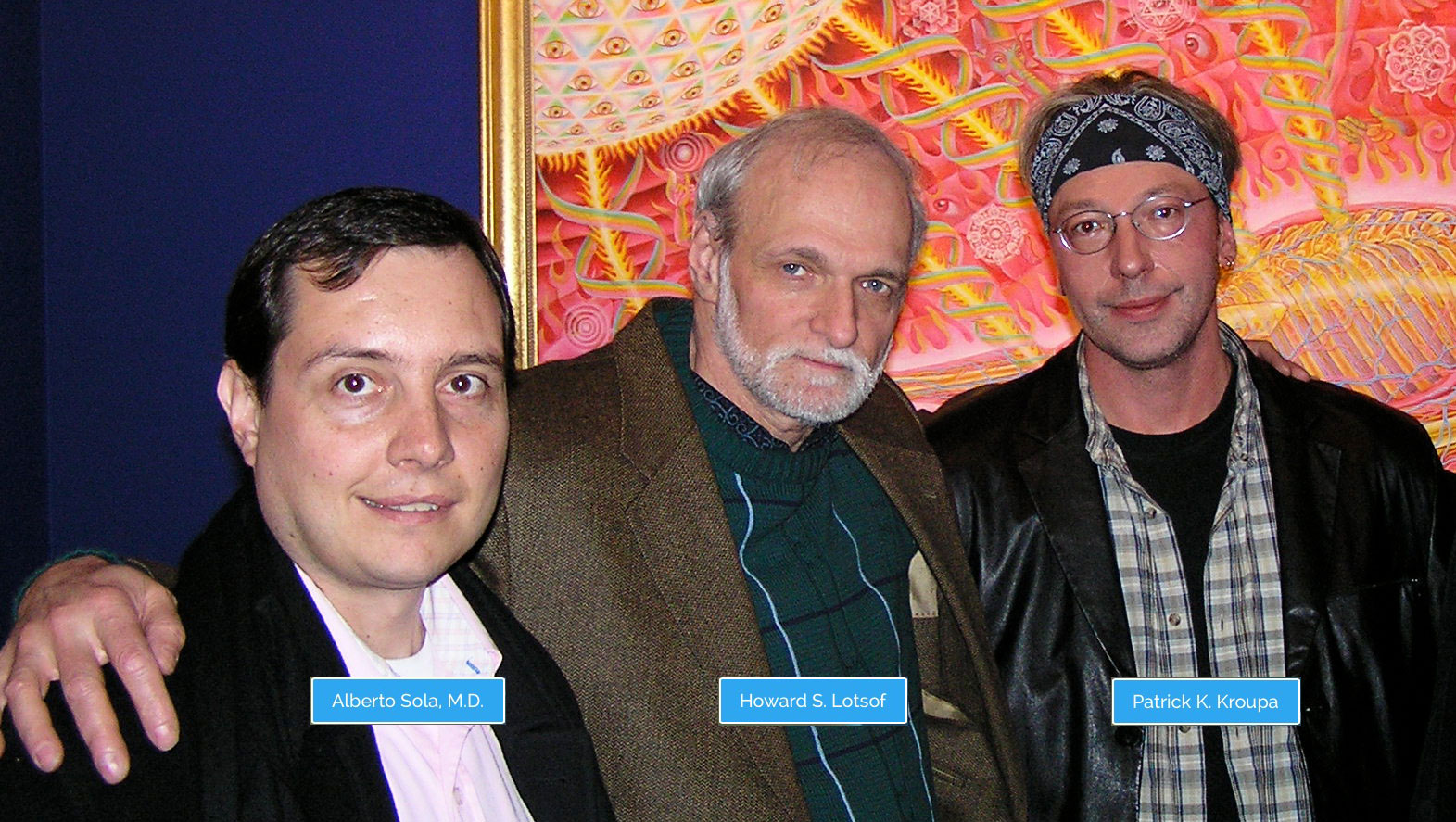

Ibogaine Evangelists (From left) Dr. Alberto Sola, Howard Lotsof, and Patrick Kroupa, are at the forefront of a growing movement.

How Ibogaine Works remains a mystery. Mash’s theory is that the alkaloid converts into the metabolite noribogaine, which fits into the brain’s opiate receptors, effectively blocking them. It wasn’t until 1962 that a young drug enthusiast and heroin addict named How- ard Lotsof accidentally discovered ibogaine’s anti-addictive properties. After tripping on ibogaine, he realized that his heroin craving dissipated without withdrawal symptoms. He then tried a crude experiment, giving ibogaine to 20 people, seven of whom were hooked on heroin. All seven reported that their physical addiction ceased after just one dose.

Over the years Lotsof fought to bring ibogaine mainstream. In 1985 he patented the drug’s use as a “rapid method for interrupting narcotic addiction syndrome.” He formed a private company that helped fund studies at Albany Medical College, which showed the drug’s efficacy on animal subjects. His company teamed up with a university-run clinic in Rotterdam, Netherlands, where ibogaine could be administered to humans. For a while the campaign seemed to be working. Both Dutch and U.S. governments monitored the trials with interest, but momentum stalled in 1993 when a patient in the Rotterdam clinic suddenly died, and the Dutch government withdrew support. (What role, if any, ibogaine played in the death remains uncertain.)

In the U.S., the National Institute on Drug Abuse was intrigued enough to initiate its own clinical studies. From 1991 to 1995, the agency spent millions on ibogaine research. But in 1995 it determined that further study would be too expensive. Alper notes that pharmaceutical companies played a key role in the government’s decision.

In 1995 Mash received FDA approval to conduct low-dose tests on cocaine-dependent human subjects at the University of Miami, but the project was stymied when she couldn’t raise grant money from either private industry or the government. Her solution was to create an offshore clinic on St. Kitts in 1996, in essence self-funding her study by treating paying customers. Mash recruited Dr. Jeffrey Kamlet, an addictionologist and former ER doctor, to assist her at the clinic. Kamlet says he was initially skeptical. “I told Deborah I wanted to see a patient using right up to the day of treatment. And afterward, if he tells me he’s not craving, I’ll believe,” he recounts. Kamlet took a patient with a $600-a-day heroin habit to St. Kitts with him. After treatment, he watched the patient simply stop using heroin. He left convinced it was the most powerful tool in existence to treat opiate dependency. Today Kamlet, the former president of the Florida Society of Addiction Medicine, says simply: “In my opinion, this is one of the most important discoveries in the history of addiction medicine.” The clinic treated about 400 patients, mostly heroin and cocaine addicts, before Mash closed it in 2005. In 2007 she submitted her data to the FDA, after it was clear that private industry would not get involved. The results, she says, were astonishing. “We demonstrated that ibogaine can be administered safely and is extremely effective.”

By then, Lotsof’s patent had expired, and the drug’s application to treat addiction entered the public domain. This was a commercial death knell as far as Big Pharma was concerned. It costs somewhere around $300 to $500 million to shepherd a prospective drug through the clinical trials required by the FDA. And no company wants to spend half a billion dollars on a product to which it will have no exclusive rights.

[Kroupa] was one of the most severe heroin addicts I have ever encountered, and he’s a unique study because he’s intellectually gifted.

–Dr. Deborah C. Mash

Even if the patents were still available, ibogaine would be a tough sell to mainstream drug manufacturers, which at first seems counterintuitive given the potential market. NIDA estimates there are as many as a million heroin addicts out there, and twice that many abusing prescription opiates like oxycodone. There are other drugs, approved by the FDA and sold commercially via prescription, that interrupt opioid signaling— most notably naltrexone (marketed as ReVia, Depade, and Vivitrol), which is used to treat alcohol and narcotic addictions, and acamprosate (marketed as Campral), which is used primarily for alcohol. All have a far less dramatic effect than the one reported by ibogaine users.

Yet ibogaine remains off-limits, primarily because no one has been able to divorce the hallucinogenic effects from its addiction-blocking properties. “The pharmaceutical giants in the world today aren’t interested in looking at hallucinogens as therapeutic entities,” says Dr.Vocci, pointing to the strong societal bias and safety concerns. (Although no causal link between ibogaine use and death has been determined, about 11 people died within 72 hours of taking the drug as a treatment between 1990 and 2006, according to Alper’s studies.) It’s also a one-treatment option, and the assumption is that drug companies like repeat customers.

In its exile, ibogaine shares the fate of other compounds stigmatized for their close association with drug culture. Psychotherapists used MDMA, commonly known as ecstasy, as a therapeutic tool for patients with mild psychiatric disorders before the drug was criminalized. And then there is the long and complex battle over the medical use of marijuana.

The idea of using a drug to reset the brain’s response to intoxicants troubles many in abstinence-based recovery communities, who believe that addiction cannot be cured with a magic bullet. Even ibogaine’s standard- bearers acknowledge that addicts have psycho- logical issues that need to be addressed. Some— Kroupa, predictably, but also the conservative Dr. Mash—think there’s some therapeutic benefit to the hallucinatory powers of ibogaine, that the trip might actually help people confront the demons in their personalities.

Kroupa likes to say he would probably be dead if it weren’t for ibogaine. “He was one of the most severe heroin addicts I have ever encountered,” says Mash. “And he’s a unique study because he’s intellectually gifted.” She was impressed enough to give him a job, which is not to say they always agreed. Mash feels strongly that the grassroots movement jeopardizes ibogaine’s slim chance of gaining legitimacy. “It’s going underground because people are desperate,” she sighs. “The point is, this works, but we’ll never be able to show that because hallucinogens have such a damaged reputation.”

The bottom line is that ibogaine gives people their lives back. And no, it’s not perfectly safe, but neither is shooting things into your veins that you cop on a street corner.

–Patrick K. Kroupa

Without government support, ibogaine’s future as a treatment lies almost solely in the hands of its shadow brigade of medical vigilantes. A few fledgling clinics have opened in Mexico, including one in Tijuana where a patient died after taking ibogaine in 2006. (According to Baja’s attorney general, the patient’s death was apparently caused by health complications unrelated to the treatment.) But these options are open only to those who can afford private care. If you’re an addict of last resort or modest means like B.G., who Kroupa reports has stayed clean, you must take to the underground.

Back at his house, smoking a Camel Wide, Kroupa takes the long view. “The purpose of a pharmaceutical company is not to cure any specific disease or help people,” he says without rancor. “The purpose of any corporation is to generate revenue. The question is not, ‘Can we solve a problem?’ It’s ‘Can we make a lot of money solving a problem?’” In this case, probably not. “You’ve got a drug that cannot be patented for drug dependence; you’ve got a single-dosage modality, you’ve got the psychedelic side effect; oh, and by the way, it’s a Schedule 1 drug offense!” He laughs. “Everything that can be stacked against ibogaine is stacked. You’re fucked.”

But like a true evangelist, he is undeterred. “If something is effective, who the fuck cares about the paperwork? The bottom line is, ibogaine gives people their lives back. And no, it is not perfectly safe, but neither is shooting things into your veins that you cop on a street corner.” For now, while the research community “spins its wheels,” Kroupa will continue to sow the seeds of revolution.

“I help the fucked get unfucked,” he says.

Recent Comments