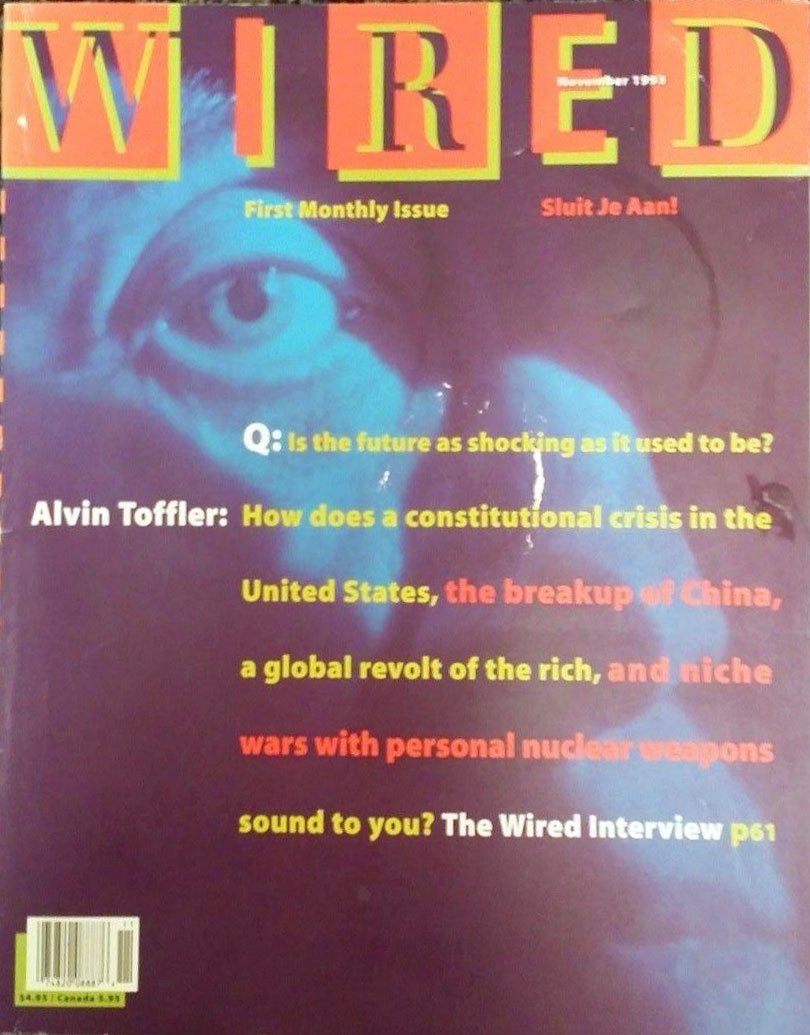

November 1993

MindVox: Urban Attitude Online

A story about a pair of outlaw hackers who turned legit.

By Charles Platt

It started as a mind game to drive nerdy kids into a feeding frenzy. It was called Phantom Access – the ultimate hacking program – and it was supposed to open up any system anywhere, from the PC clone in the high-school records office to the mainframes at Strategic Air Command. It was written by a kid in New York named Patrick Kroupa, who had a bad attitude, delusions of grandeur, and a rich fantasy life – which made him only slightly different from his fellow hackers in the early 1980s.

Back then, the online world was a lawless frontier. Kids set up bulletin boards such as The Safe House, The Legion of Doom, The Magic Chalice, and The Adventurers’ Tavern. They waged battles, staged raids, crashed each other’s systems, and jousted on the Net.

Phantom Access was the ideal tool for this quasi-legal obsession, according to Patrick (who called himself Lord Digital). He said its features were so fantastic, they couldn’t even be implemented on existing hardware. But he never sent out the program. That was the mind game: to drive kids crazy with the prize they couldn’t have, the Holy Grail of hacking.

Meanwhile, also in New York City, there was Bruce Fancher, who looked too neat, clean, and classy to be a hacker. He parted his hair on the side, wore oxford shirts, and kept his black shoes highly polished. But Bruce enjoyed the cut-and-thrust of online jousting as much as anyone, and each day after school he swung by the phone company and went through their garbage, looking for switching-system documentation that he could trade with his friends from the Legion of Doom, who met at the local Burger King.

Bruce got to know Patrick via modem. With extreme difficulty, he finally obtained a copy of Phantom Access. The fantastic features, of course, were missing, so Bruce added one of his own – one that would trash a user’s hard drive the tenth time the program was invoked. Then, with a smile, he started giving it away.

That was back in the early 1980s, before viruses were illegal. Fast- forward.

By the late ’80s the modem world had been rehabilitated. Tens of thousands of legitimate bulletin boards sprang up across America, as safe and dull as tract homes.

Bruce was studying history in his second year at Tufts University. Patrick, meanwhile, had come out of a retreat in New Mexico. Having met all of his ambitions at the age of 21, he had found himself unfulfilled and unhappy. He’d developed an obsession with body-building. Five-hour-a-day workouts, insane diets, and steroids left him bigger, stronger, but no more content. Ultimately, he dropped acid, found enlightenment, and returned to New York.

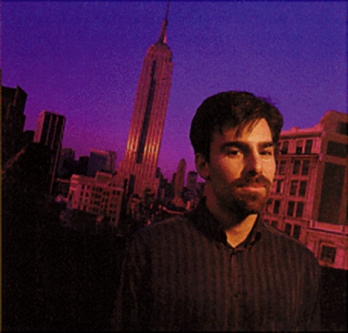

They seemed an unlikely pair – Bruce the calm, quiet conformist; Patrick, long-haired with baggy old clothes and a dreamy, spacey look. Still, they shared a feeling of ironic detachment and frank disgust for the terminal dullness of the modern modem world. It was time, Patrick said, for them to put together their own board; to recreate the fun and freedom of the early days on powerful new hardware instead of the Apple IIs they used to use.

Bruce reluctantly agreed, and they named their new board MindVox.

Many of their old-time hacking friends had been hauled off in handcuffs, so they decided to make this a legitimate business. Bruce contributed the money he’d been saving for the rest of his education; his father and Patrick’s family added some as well. Only one trace of their past survived, as a sly joke: They named the parent corporation Phantom Access Technologies.

In July 1992, MindVox – an online hangout for folks like these two – went into beta testing. In November 1992, they were online. Patrick posted a long editorial (see excerpt, page 58) describing what he’d seen and been through: the dark side of cyberspace, the hostility and alienation that had soured the playfulness of the 1980s. His sincere, self-revealing tone struck a nerve. MindVox started attracting users.

Today it runs on a couple of Sun SPARCstation 2s, has a dedicated 56Kbit Internet link, and a T1 line. It runs out of a little white-walled, fluorescent-lit, renovated office in an old cast-iron building in midtown Manhattan. There’s a mess of wires and a cluttered, homey, back-room feel. Art on the walls reflects the owners’ obsessions: telephones (Bruce) and psychedelia (Patrick). Presiding over the scene is a small, rubberized fig- ure of Star Trek’s Mr. Spock with his arms raised in benediction.

But the important reality is inside the computers. Here is a forum hosted by US Treasury agent Kim Clancy, in which you can debate electronic freedom with the feds. Here the entire semi-reformed Legion of Doom logs on. Here are labyrinthine text archives on topics such as anarchy, psychedelic drugs, and computer viruses. And here is a huge text library transcribed from old Apple II diskettes – a complete history of online communication all the way back to the 1970s.

“It’s a unique community,” says Richard Jones, one of a crew of volunteers who helped set up the system. “Other boards don’t have such a distinctive character. They’re like airport terminals. If an airport terminal burned down, you wouldn’t care, you’d switch to a different airport. But if MindVox went offline, a lot of people would be homeless.”

Another board based in New York – Echo, run by Stacy Horn – claims an equal sense of community. “But they’re not an open system,” Richard says. “They’re very politically correct. You can’t talk about drugs or anarchy, for in- stance. You’ll get a letter telling you not to offend people.”

“MindVox is the only national board where people can express them- selves as they actually talk in real life,” says “Voidmaster,” a user who telnets in from Hollywood. “It’s a smart-aleck, wise-cracking, nonconformist soapbox. And it’s full of creative people.”

That much is true: A lot of artists, writers, and musicians are online. Wil Wheaton from Star Trek: The Next Generation is at MindVox regularly. Billy Idol mentions MindVox on his new Cyberpunk CD. And Kurt Larson, lead singer and lyricist for Information Society, has been known to shout out his MindVox e-mail address at rock concerts.

More than any board before it, MindVox has actually become fashionable – a sought-after commodity, like Patrick’s old hacking program.

Not everyone feels happy about the talent for self-promotion that made this happen. Alexis Rosen, who runs a competing board in New York, complains that MindVox is “all hype, no substance,” and he tut-tuts over its incomplete range of Internet services.

“He’s a techie; he’ll never understand it,” says Patrick. “Most Unix boards just put up a generic public access site and type ‘make’ on a bunch of utilities they downloaded from somewhere, and wonder why nobody cares.”

“But Unix is arcane,” says Bruce, “and it’s weird, and most users don’t want to deal with it. That’s why we spent so much time and trouble putting a shell around it, so users don’t have to deal with it.”

The “shell” he’s talking about is an easy-to-use interface with lots of on- line help and a powerful, flexible set of menus and commands. Bruce takes credit for this, having done most of the system design. “I’m still improving the software,” he says, “and I want the content of the board to get broader – provided we can keep that edge of bohemianism, or whatever you want to call it.”

But bohemianism has its limits, and irony has no end. On MindVox, everything has to be legal. There’s even a security expert who constantly monitors the system to keep the next generation of rogue hackers out. The lawless era of online jousting is long gone.

“Back then,” says Patrick, “we pretty much behaved like assholes. Today, we have legitimate access to most of the things we want. So we have no incentive to take things that don’t belong to us. Plus, we grew older and realized that some of the things we were doing were unacceptable.”

“All I’m interested in right now,” says Bruce, “is providing the best possible online service. I grew up using a modem. I used to get up at 5AM every day, so I could have exclusive use of the phone line at home before I went to school. So I was fated to do this. It’s more than a business, which is why we put in twelve- and fourteen-hour days. It’s messed up the rest of my life completely, and I often sleep at the office. But it’s what I want to do.”

MindVox now boasts nearly 3,000 users and expects to keep right on growing, with 64 lines and full T1. Before the end of the year, it will offer local access from all over the country, feeding in through their leased-line Internet connection.

Currently, MindVox offers unlimited connect time for US$15 per month. For information call (800) 646 3869, or telnet to (phantom.com). To dial direct, set your modem to 8 data bits, no parity, and 1 stop bit, then dial +1 (212) 989 4141.

Recent Comments