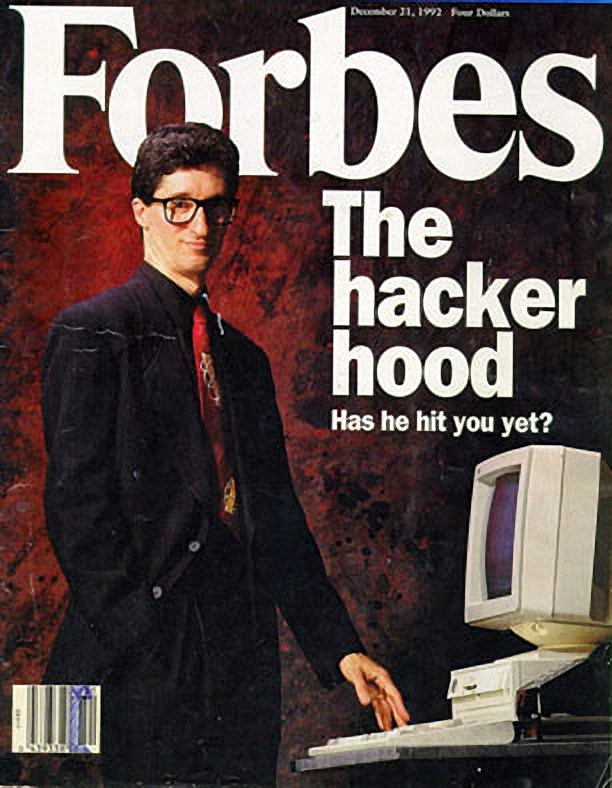

The playground bullies are learning how to type.

(Computer hacker crime wave.)

William G. Flanagan

Dec 21 1992, v150, n14, p184(6)

COPYRIGHT Forbes Inc. 1992

Leonard Rose, a 33-year-old computer consultant and father of two, is also a felon. He recently completed 81/2 months in a federal prison camp in North Carolina, plus 2 months in a halfway house. His crime? Passing along by computer some software code filched from Bell Labs by an AT&T employee. Rose, who now lives in California, says he is still dazed by the harsh punishment he received. “The Secret Service,” he says, “made an example of me.”

Maybe so. But if so, why are the cops suddenly cracking down on the hackers? Answer: because serious computer crime is beginning to reach epidemic proportions. The authorities are struggling to contain the crimes, or at least slow their rapid growth.

Rose agrees the hacker world is rapidly changing for the worse. “You’re getting a different sort of person now,” he says of the hacker community. “You’re seeing more and more criminals using computers.”

One well-known veteran hacker, who goes by the name Cheshire Catalyst, puts it more bluntly: “The playground bullies are coming indoors and learning how to type.”

Rose and the Cheshire Catalyst are talking about a new breed of computer hackers. These aren’t just thrill-seeking, boastful kids, but serious (if boastful) cybercrooks. They use computers and telecommunications links partly for stunt hacking–itself a potentially dangerous and costly game–but also to steal valuable information, software, phone service, credit card numbers and cash. And they pass along and even sell their services and techniques to others–including organized crime.

Hacker hoods often exaggerate their escapades, but there is no doubt that their crimes are extensive and becoming more so at an alarming rate. Says Bruce Sterling, a noted cyberpunk novelist and author of the nonfiction The Hacker Crackdown (Bantam Books, 1992, $23): “Computer intrusion, as a nonprofit act of intellectual exploration and mastery, is in slow decline, at least in the United States; but electronic fraud, especially telecommunications crime, is growing by leaps and bounds.”

Who are these hacker hoods and what do they do for a living? Take the 19-year-old kid who calls himself Kimble–he is a very real person, but for reasons that will become clear, he asks us to mask his identity.

Based in Germany, Kimble is the leader of an international hacker group called Dope. He is also one of the most celebrated hackers in his country. He has appeared on German Tv (in disguise) and is featured in the December issue of the German magazine Capital.

From his computer terminal, Kimble spends part of each day cracking PBX systems in the U.S., a lucrative form of computer crime. PBXs are the phone systems businesses own or lease. Hackers break into them to steal access numbers, which they then resell to other hackers and, increasingly, to criminals who use the numbers to transact their business. These are hardly victimless crimes; businesses that rightfully own the numbers are expected to pay the billions of dollars of bogus phone bills charged on their stolen numbers each year (Forbes, Aug. 3).

Kimble, using a special program he has written, claims he can swipe six access codes a day. He says he escapes prosecution in Germany because the antihacking laws there are more lax than in the U.S. “Every PBX iS an open door for me,” he brags, claiming he now has a total of 500 valid PBX codes. At Kimble’s going price of $200 a number, that’s quite an inventory, especially since numbers can be sold to more than one customer.

Kimble works the legal side of the street, too. For example, he sometimes works for German banks, helping them secure their systems against invasions. This might not be such a hot idea for the banks. “Would you hire a former burglar to install your burglar alarm? ” asks Robert Kane, president of Intrusion Detection, a New York-based computer security consulting firm.

Kimble has also devised an encrypted telephone that he says cannot be tapped. In just three months he says he has sold 100.

Other hacker hoods Forbes Spoke to in Europe say they steal access numbers and resell them for up to $500 to the Turkish mafia. A solid market. Like all organized crime groups, they need a constant supply of fresh, untraceable and untappable telephone numbers to conduct drug and other illicit businesses.

Some crooked hackers will do a lot worse for hire. For example, one is reported to have stolen an East German Stasi secret bomb recipe in 1989 and sold it to the Turkish mafia. Another boasted to Forbes that he broke into a London police computer and, for $50,000 in deutsche marks, delivered its access codes to a young English criminal.

According to one knowledgeable source, another hacker brags that he recently found a way to get into Citibank’s computers. For three months he says he quietly skimmed off a penny or so from each account. Once he had $200,000, he quit. Citibank says it has no evidence of this incident and we cannot confirm the hacker’s story. But, says computer crime expert Donn Parker of consultants sri International: “Such a ‘salami attack’ is definitely possible, especially for an insider.”

The tales get wilder. According to another hacker hood who insists on anonymity, during the Gulf war an oil company hired one of his friends to invade a Pentagon computer and retrieve information from a spy satellite. How much was he paid? “Millions,” he says.

Is the story true? The scary thing is, it might well be.

No one knows for sure just how much computer crime costs individuals, corporations and the government. When burned, most victims, especially businesses, stay mum for fear of looking stupid or inviting copycats. According to Law and Order magazine, only an estimated 11% of all computer crimes are reported.

Still, the FBI estimates annual losses from computer-related crime range from $500 million to $5 billion.

The FBI is getting more and more evidence that the computer crime wave is building every day. Computer network intrusions–one way of measuring attempted criminal cracking of computer systems–have risen rapidly. According to USA Research, which specializes in analyzing technology companies, hacker attacks on U.S. workplace computers increased from 339,000 in 1989 to 684,000 in 1991. It’s estimated that by 1993, 60% of the personal computers in the U.S. will be networked, and therefore vulnerable to intrusion.

While companies dislike talking about being ripped off by hackers, details sometimes leak out. In 1988, for instance, seven men were indicted in U.S. federal court in Chicago for using phony computer- generated transactions to steal $70 million from the accounts of Merrill Lynch, United Airlines and Brown-Forman at First National Bank of Chicago. Two pled guilty; the other five were tried and convicted on all counts.

According to generally reliable press reports, here are some other ways computer criminals ply their trade: * In 1987 Volkswagen said it had been hit with computer-based foreign-exchange fraud that could cost nearly $260 million. * A scheme to electronically transfer $54 million in Swiss francs out of the London branch of the Union Bank of Switzerland without authorization was reported in 1988. It was foiled when a chance system failure prompted a manual check of payment instructions. * Also in 1988, over a three-day period, nearly $350,000 was stolen from customer accounts at Security Pacific National Bank, possibly by automated teller machine thieves armed with a pass key card. * In 1989 irs agents arrested a Boston bookkeeper for electronically filing $325,000 worth of phony claims for tax refunds. * In 1990 it was reported that a Malaysian bank executive cracked his employer’s security system and allegedly looted customer accounts of $1.5 million. * Last year members of a ring of travel agents in California got two to four years in prison for using a computer reservation terminal to cheat American Airlines of $1.3 million worth of frequent flier tickets.

U.S. prosecutors say that members of a New York hacker group called MOD, sometimes known as Masters of Deception, took money for showing 21 -year-old Morton Rosenfeld how to get into the computers of TRW Information Services and Trans Union Corp. Caught with 176 credit reports, Rosenfeld admitted selling them to private investigators and others. In October he was sentenced to eight months in prison.

The newest form of cybercrime is extortion by computer–give me money or I’ll crash your system. “There’s no doubt in my mind that things like that are happening,” says Chuck Owens, chief of the FBI’s economic crime unit. But Owens won’t talk about ongoing cases.

Many hackers are young, white, male computer jocks. They include genuinely curious kids who resent being denied access to the knowledge- rich computer networks that ring the globe, just because they can’t afford the telephone access charges. (To satisfy their needs in a legitimate way, two smart New York young hackers, Bruce Fancher and Patrick Kroupa, this year started a widely praised new bulletin board called MindVox — modem: 212-988-5030. It’s cheap and allows computer users to chat, as well as gain access to several international computer networks, among other things.)

Then there are the stunt hackers. Basically these are small-time hoods who crash and occasionally trash supposedly secure computer networks for the sheer fun of it. They swap and sell stolen software over pirate bulletin boards. One of these hackers sent Forbes an unsolicited copy Of MS-DOS 6.0–Microsoft Corp.’s new operating system, which isn’t even scheduled to be on the market until next year. It worked fine. (We first had it tested for viruses with Cyberlock Data Intelligence, Inc. in Philadelphia, an electronic data security firm with a sophisticated new hardware-based system that’s used to detect viruses.)

The more malicious stunt hackers like to invade company voice mail systems and fool around with so-called Trojan horses, which can steal passwords and cause other mischief, as well as viruses and other computer-generated smoke bombs, just to raise hell.

This kind of hacking around can wreak tremendous damage. Remember. Robert Tappan Morris. In 1988 Morris, then a 22-year-old Cornell University grad student, designed a worm computer program that could travel all over computer networks and reproduce itself indefinitely. Morris says he meant no harm. But in November 1988 Morris released the worm on the giant Internet computer network and jammed an estimated 6,000 computers tied into Internet, including those of several universities, NASA and the Air Force, before it was stopped. Damages were estimated as high as $185 million.

That event was something of a watershed for the law enforcement people. In 1990 Morris was one of the first hackers to be convicted of violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986. He could have been sentenced to five years in prison and a $250,000 fine. Instead, Morris got just three years’ probation, a $10,000 fine, 400 hours of community service and had to pay his probation costs. Today he’d probably be thrown in the slammer.

After the curious kids and the stunt hackers, a third element in the hacker underworld is made up of members of organized crime, hard-core cybercrooks, extortionists, shady private investigators, credit card cheats, disgruntled ex-employees of banks, telephone and other companies, and various computer-savvy miscreants. These are computer thugs who hack for serious dollars, or who buy other crooked hackers’ services and wares.

One of the peculiarities of hackers is that many cannot keep their mouths shut about their illegal exploits. They boast on their underground bulletin boards and in their publications about all the nasty things they can, and occasionally do, pull off. They brag to the press and even to the authorities. Witness Germany’s Kimble and the many other hacker hoods who talked to Forbes for this article.

Over their own underground bulletin boards, hackers have brazenly broadcast all kinds of gossip, software and trophy files brought back like scalps from intrusions into other people’s computers. The most infamous example is the 911 file purloined from BellSouth, which prosecutors said had key information about the vital 911 emergency telephone network. The file turned out to be far less valuable than alleged. Nonetheless, its theft and, later, its mere possession got a whole raft of hackers–including a group called the Legion of Doom–in big trouble. Over the past three years, several of them have been busted and their computer equipment seized. A few drew stiff jail terms.

The hackers even have their own above-ground magazines. One, 2600, the Hacker Quarterly, is sold on newsstands. In the current issue, there is an article on how to crack COCOTS, customer-owned, coin-operated telephones, and get free long distance service. While the publisher of 2600 advises readers not to try such schemes, the easy-to-follow instructions are right there, in black and white.

The publisher of 2600, Eric Corley (alias Emmanuel Goldstein), claims that he is protected by the First Amendment. But readers who follow some of the instructions printed in 2600 magazine may find themselves in deep trouble with law enforcement. Notes senior investigator Donald Delaney, a well-known hacker tracker with the New York State Police: “He hands copies out free of charge to kids. Then they get arrested.”

An even bolder magazine, Hack-Tic, is published by Rop Gonggrijp in Amsterdam, a hacking hotbed thanks in part to liberal Dutch laws. Hack- Tic is something like 2600, but with even more do-it-yourself hacking information. The hacker hoods stage their own well-publicized meetings and conventions, which are closely watched by the authorities.

On the first Friday of every month, for example, at six cities in the U.S., 2600 magazine convenes meetings where hackers can, in the words of the magazine itself, “Come by, drop off articles, ask questions, find the undercover agents.” Forbes dropped by 2600’s Nov. 6 meeting in New York. It was held in the lobby of the Citicorp Center on Lexington Avenue, a sort of mini urban mall, with lots of pay phones–phones are to hackers what blood vessels are to Dracula.

On this particular Friday the two or three dozen attendees consist mainly of teenage boys and young men wearing jeans and T shirts and zip- up jackets. Most are white, though there are some blacks and Asians. Most of these young people pretty much resemble the kids next door–or the kids under your own roof. A few look furtive, almost desperate.

Moving easily among the kids are a few veteran hackers–and, watching them, some well-known hacker trackers, sometimes even New York State Police’s Don Delaney. He might lurk on one of the upper levels of the Citicorp Center or stroll past the pay phones looking for a suspect wanted in New York. Don’t the suspects stay away? Not necessarily. At one meeting Delaney walked right past three young men he had arrested, and not one of them even noticed him. “They’re in their own world,” he explains.

On the edge of the crowd stands a slight, intense young man wearing an earring and a neatly folded blue bandana around his head. Twenty-year- old Phiber Optik, as he calls himself, is currently under federal indictment in New York, charged with sundry computer crimes. According to federal authorities, he and other members of the hacker group called MOD sold access to credit reporting services and destroyed via computer a televesion station’s educational service, among other things. Phiber Optik claims that he’s innocent.

As the group grows, 2600 publisher Corle makes a dramatic entrance. He looks as if he’s in his mid-30s and wears 1960s-style long black hair. A baby-faced assistant stands at his side, selling T shirts and back issues of 2600 magazine.

Now and then Corley darts to the pay phones to take phone calls from other hacker meetings around the world. After takin one call he turns around with a worried look. He has just heard that the 2600 meeting at a mall in Arlington, Va. was busted by mall security and the Secret Service. Authorities there demanded the names of the two dozen or so attendees, confiscated their bags containing printouts and computer books, and booted them out of the mall.

The group in Arlington was lucky compared with what happened to some hackers attending “PumpCon,” a hacker convention held at the Courtyard by Marriott in Greenburgh, N.Y., over the recent Halloween weekend. Responding to a noise complaint, the police arrived, then got a search warrant and raided the hackers’ rooms. The cops confiscated computer equipment and arrested four conventioneers for computer crimes. Three were held in lieu of $1,000 bail. No bail was set for the fourth, a 22- year-old wanted for computer fraud and probation violation in Arizona.

Around the country, computer users of every stripe are growing concerned that law enforcement officials, in their zeal to nail bigtime cybercrooks and computer terrorists, may be abusing the rights of other computer users. In some cases, users have been raided, had their equipment confiscated, yet years later still have not been charged with any wrongdoing–nor had their equipment returned.

In 1990 Lotus Development founder Mitchell Kapor and Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow, with help from Apple Computer cofounder Stephen Wozniak and John Gilmore, formerly of Sun Microsystems, started a nonprofit group called the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). Its aim is to defend the constitutional rights of all computer users.

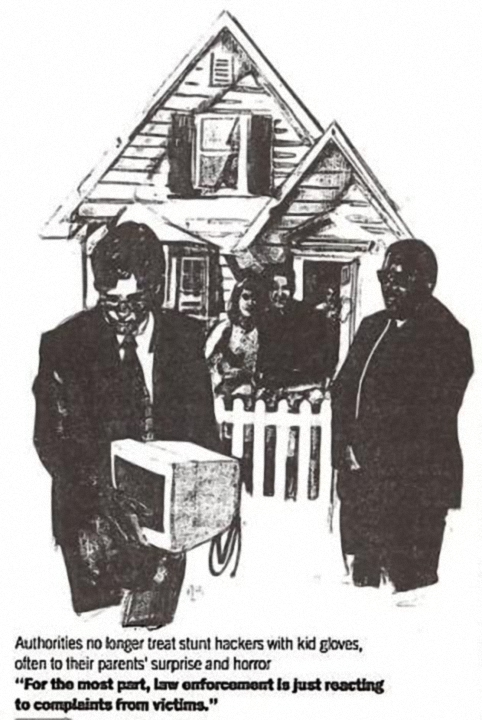

But if you know someone who likes to hack around, pass along this advice to her or him: While it is a common myth among hackers that the authorities will let them go if they reveal how they accomplished their mischief, the days of such benign treatment have disappeared as the computer crime wave has built.

“If it’s a crime, it’s a crime,” warns the New York State Police’s Don Delaney. “The laws are there for a good reason. For the most part, law enforcement is just reacting to complaints from victims.”

Recent Comments